I’m sure the old platitude that ‘Christmas comes earlier every year’ is true. The Christmas tree went up in our town square two weekends ago, there is a steady stream of junk email flowing into my inbox exhorting me to ‘Get ready for Christmas!’, and – halfway through November – I’ve already seen my first group of carol singers in Oxford city centre. Accompanying the carol singers was another noise that many associate just as closely with the pre-Christmas season: a small child howling on a shop floor, a red-faced parent looking on as their bundle of joy delivers a passionate homily on the unfairness of life and the shocking inhumanity of it all. For hovering alongside the ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future is the spectre of over-indulgence.

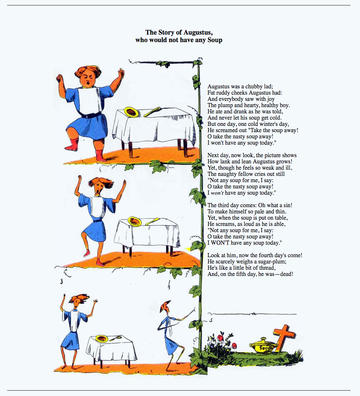

The spoiled child is not just a product of the modern technological age, however, hankering after iPads and internet-connected dolls (yes, really – the horror film potential of My Friend Cayla is enormous). Pampered children are figures often found in nineteenth-century novels, or satirised in ‘cautionary tales’ such as the iconic Struwwelpeter, in which Augustus (the boy who would not have any soup, above) wastes away to a skeleton as a result of his fussiness. Stories in popular magazines depicted fictional children like those of the ‘Pimento family’ as ‘torturations’ running riot through the house and oblivious to the comfort of others:

Master Alfred could rant the soliloquies in Douglas, and, to shew the versatility of his genius, perform “Little Pickle,” with an additional scene … in which he set fire to a chintz curtain, broke some china chimney-ornaments, upset a dumb-waiter, and fired a cracker under the chair of his indulgent papa. (Anon, ‘The Pimento Family; or, Spoiled Children’, Monthly Magazine, June 1829).

Besides his or her comedic value, though, the spoiled child had a more serious side, as André Théodore Brochard suggested when he included a section on the matter in his 1865 book, Sea-Air and Sea-Bathing for Children and Invalids:

These cases too often depend upon the culpable weakness of the parents. Much more common than is generally supposed, they present a set of symptoms which it is the most difficult thing in the world to relegate to any particular organ or seat. To give them a name, which shall embrace in one term all their multitudinous, though almost identical, causes, I shall call it the disorder of spoiled children.

‘The disorder of spoiled children’, caused by over-indulgent parents who pandered to their child’s every whim, could cause a whole host of unpleasant bodily and mental effects. ‘Depraved appetites’ – for nothing but chocolate, or unripe vegetables – led to altered constitutions, the child becoming ‘lymphatic, scrofulous, and often consumptive’. There were also longer-term psychological effects of spoiling: the child indulged by his parents is given a rude awakening when he grows up, discovering that not everyone finds him so enchanting as his permissive mother and father:

…suffering under an accumulation of real and fancied ills, his misery becomes so great and insupportable, that sullen or furious insanity, or dreadful suicide may soon be expected to succeed. (James Parkinson, Observations on the excessive indulgence of children, particularly intended to show its injurious effects on their health, and the difficulties it occasions in their treatment during sickness, 1807).

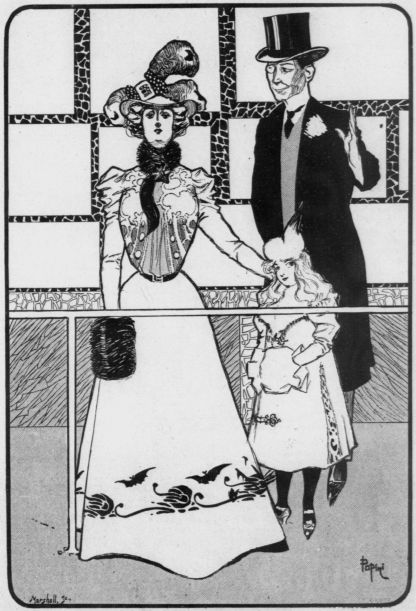

Many articles placed the blame for spoiled children firmly on the heads of the parents, but particularly mothers, demonstrating that anxieties about the place of motherhood in modern life are far from a modern phenomenon. ‘In the mad race after pleasure and excitement now going on, ‘ wrote The Saturday Review in 1868, ‘the tender duties of motherhood have become simply disagreeable restraints’. Women of the middle and upper classes, caught up in new consumer society, were said to dress their children in expensive new fashions and send them to even more expensive schools, but neglect their simple moral education, instead handing them over to governesses and nurses. A short story in The London Reader of 1865, ‘The Spoiled Child’, was explicit about the potentially dire consequences of such behaviour, following young Harry Hillgrove whose early spoiling leads him to theft and alcoholism in later life. He abandons his mother and turns to a life of crime, but Mrs Hillgrove’s parenting mistakes come back to haunt her when Harry breaks into her house; she dies from shock and Harry, reflecting upon his mistakes, commits suicide.

Nineteenth-century concerns for spoiled children were not simply the stuff of sensation fiction, but drew upon contemporary ideas about the development of the nervous system and laws of heredity, considering how the process of growing up might literally – and permanently – alter the fabric of the body and brain. The most thoughtless thing that parents could do, both for the future happiness of their offspring and for the good of society more generally, was to indulge their children in ‘lumps of sugar’, ‘wine as a treat’, or ‘heated and unhealthy amusements during the holidays’. The problem was bringing the parent to recognise the folly of their behaviour. As a joke in The London Journal wryly observed:

“There’s one good thing about spoiled children.”

“What’s that?”

“One never has them in one’s own house.”