Jean-Michel Johnston joined the project in October 2017. He researches the impact of telegraphy in nineteenth-century Europe.

The better-known story of electrical telegraphy narrates the triumphant onward march of a revolutionary new means of communication during the nineteenth century. It begins with the experiments in electro-magnetism conducted by Samuel Morse, Charles Wheatstone and Werner Siemens, among others, whose inventions led governments and the private sector to build telegraph lines across Europe and North America during the 1850s. In 1866, the first fully operational submarine telegraph cable was laid across the Atlantic, and soon these ‘tentacles of progress’ were extending across the globe.[1] Governments, companies and the general public became avid users of an expanding worldwide network of communication, intensifying and accelerating a process of unrelenting globalisation which continues to this day.

My research aims to uncover the lesser-known twists and turns in this narrative, to explore both the hopes and the frustrations, the anxieties as well as the excitement which were associated with telegraphy in nineteenth-century Europe. ‘Distance exists no more!’ a German illustrated periodical declared in 1853, echoing the public perception in Europe that the speed of telegraphic communication would ‘annihilate’ space and time.[2] But others were soon more sceptical. In 1869, the American neurologist George Miller Beard held the technology partly responsible for the crisis of ‘neurasthenia’, of anxiety, fatigue, and depression which was gripping society. By the turn of the twentieth century, denunciations of the stresses caused by modern communication and transport technologies competed with calls for ever faster, ever more pervasive network connections.

How did this ‘tempo virus’, this insatiable need for speed, spread through European society during the nineteenth century?[3] Was it a new phenomenon, or did it draw on existing desires and concerns? To answer these questions, it is important to compare the expectations which Europeans placed in telegraphy with their experience in using the technology. Communication between Paris and St Petersburg might take place in a matter of minutes, but this could make the 20-minute trek down to the local telegraph office seem all the more onerous. The speed of business transactions between stock exchanges was greatly enhanced by the technology, and they were based upon increasingly reliable and up-to-date sources of information. All the more concern, then, when weather conditions, wars, or technical faults interrupted or delayed these exchanges. At the same time, as networks expanded the social and economic gap between the telegraphically-endowed and those who remained beyond its reach continued to grow.

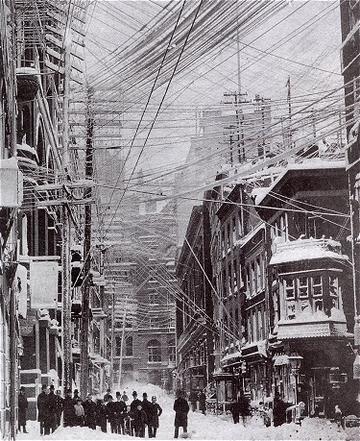

Telephone, telegraph, and power lines over the streets of New York City, 1888. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Telegraphy also introduced a host of new sights, sounds, and practices which stimulated the European imagination. The wires connecting towns and villages began to carve out the urban and rural landscape. ‘In windy weather’, wrote one British contemporary, ‘the electric wires form an Eolian harp, which occasionally emits most unearthly music’.[4] In Austria, as Amelia Bonea has discovered, these sounds inspired the compositions of Johann Strauss II. The habit of formulating concise, cost-efficient dispatches, meanwhile, produced a new ‘telegraphic’ writing style. ‘It is a very curious fact’, our earlier British witness opined, ‘that a lawyer under the [Electric Telegraph] Company’s galvanic influence, is suddenly gifted with a description of clairvoyance which enables him to write on any subject in a laconic style, which in his chambers he would consider… to be utterly impracticable!’.[5]

But the same transformations were also the source of new anxieties. Was the electricity conducted by telegraph wires a public danger? Would it permeate the ground beneath them, where crops were being cultivated? What to make of the many birds which, it was reported, were regularly discovered, lying decapitated under these telegraphic gallows?[6] Not to mention that the strange tones emanating from the ‘Eolian harp’ could also be considered an unwelcome intrusion into the peaceful soundscape of rural Europe. And as Otto von Bismarck demonstrated in his careful editing of the Ems Dispatch in 1870, the curtness of the new telegraphic writing style could have devastating consequences…

We hear echoes of this blend of enthusiasm and concern in present-day attitudes to communications technologies. New media repeatedly promise to bring us ‘closer together’, but then find themselves under attack for their role in polarising public opinion. The internet and smartphones are blamed for breaking down the barrier between work and leisure time, yet obtaining greater bandwidth and faster, uninterrupted connections remains a pressing concern for many users. The consequences of brevity in communication, meanwhile, remain the subject of debate, as recent changes to Twitter’s 140-character limit demonstrated. Investigating both the expectations and the realities of telegraphic communication will help uncover the historical background to this ambiguous experience of modern life.

[1] D. R. Headrick, The Tentacles of Progress: Technology Transfer in the Age of Imperialism, 1850-1940 (Oxford, 1988).

[2] Die Gartenlaube (1853), p. 74.

[3] P. Borscheid, Das Tempo-Virus: Eine Kulturgeschichte der Beschleunigung (Frankfurt, 2004).

[4] F. B. Head, Stokers and Pokers, 3rd edn. (London, 1849), p. 126.

[5] ibid., p. 114.

[6] ibid., p. 126.