Death and Disease Behind the Counter

This term, the Diseases of Modern Life team showcased their research at two major public engagement events – our Victorian Speed Late at the Museum of the History of Science and Victorian Light Night with The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities. Both provided great platforms for me to share my new research on ill-health and retail work in the late nineteenth century, and to chat to the public about work-life balance then and now.

At both events I ran an activity called ‘Death and Disease Behind the Counter’ – a title taken from Thomas Sutherst’s 1884 book of the same name. Sutherst was a barrister who campaigned to improve living and working conditions for shop assistants. His book brings together a range of stories (allegedly) from shop workers, which highlight the overwork endemic in the retail industry. While many people today are aware of the brutalities of Victorian factory work, few know about the pressures that faced shop assistants – my aim was to bring this issue into the public consciousness.

Alison talks to visitors at Victorian Light Night. Photo by Stuart Bebb.

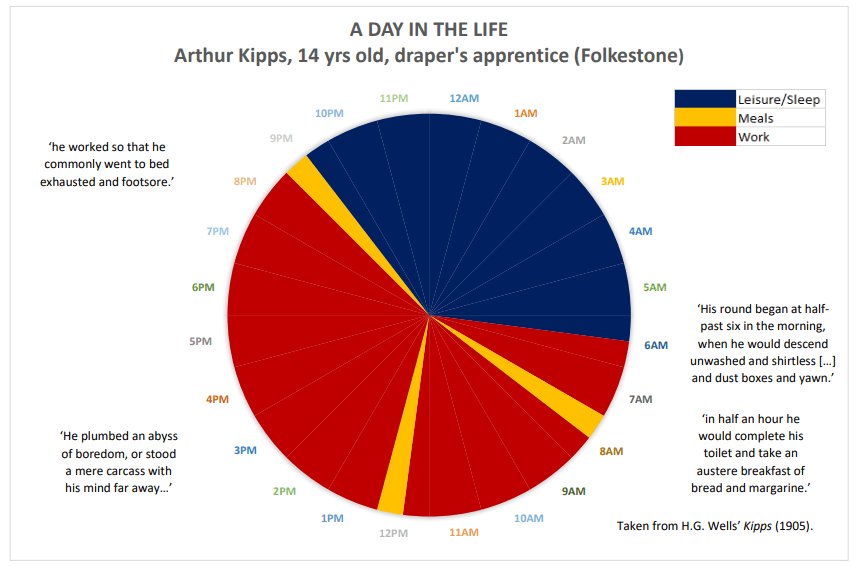

For the Victorian Speed event we were focusing on time pressures, so I devised an activity that explored a ‘Day in the Life’ of the Victorian shop assistant. I identified a range of case studies to share, drawing on primary sources including literature, journalism, life-writing, and campaigning material such as Sutherst’s book. In prepping materials for the activity, I had to get to grips with Excel (long forgotten since my schooldays) so I could devise pie charts divided into 24 hours to represent the day. I split the charts into different categories, logging how much time each of my case study shop workers spent on sleep/leisure, meals, and work. Given the nature of the sources, it was difficult to plot any more granular details, though we know that the evening entertainments available to shop workers ranged from reading periodicals to visiting the pub or music-hall. Alongside the pie charts, I included quotes from my primary sources that conveyed some of the pressures of retail work, such as how assistants felt towards the end of the day, after 12 or more hours standing on their feet, with minimal breaks.

This pie chart plots a typical day in the life of Arthur Kipps, the 14 year-old apprentice in H.G. Wells's 1905 novel Kipps.

These pie charts were a great way to engage people in conversations about the working life of Victorian shop assistants. Members of the public were divided over whether the average working days looked hellish or manageable. Some were shocked at how young the apprentices were, and how they often bore the brunt of the work (starting early to clean the shop floor). One of my examples was the author H.G. Wells, whose autobiography records his experiences of entering shop work at 13. Many people were also surprised to discover how long Victorian shops were open for – I explained that businesses seeking to attract working-class customers often stayed open late into the evenings to pick-up trade from people travelling home after work. On the other hand, some visitors noted that there were few arduous commutes shown on the pie charts. Only one of my case studies – an unnamed female assistant in a baker’s shop – described how unpaid overtime risked her missing the last journey home. Some of my visitors said that at least shop assistants had a designated time set aside for meals (typically 15-20 minutes) while they snatched their lunch breaks at their desks.

The main message I wanted to communicate, however, was that the apparent separation between work and leisure was, in many ways, misleading. The vast majority of shop assistants lived on-site, in accommodation provided by their employers. They often shared rooms (perhaps even beds) with their colleagues, ate food chosen by their employers, and lived under rules imposed by their boss (with fines for breaking curfew, for example). After hearing this, many participants conceded that the Victorian shop worker was even less fortunate than they’d supposed. We talked about the emotional pressures of living and working in one space, possibly without a sense of freedom.

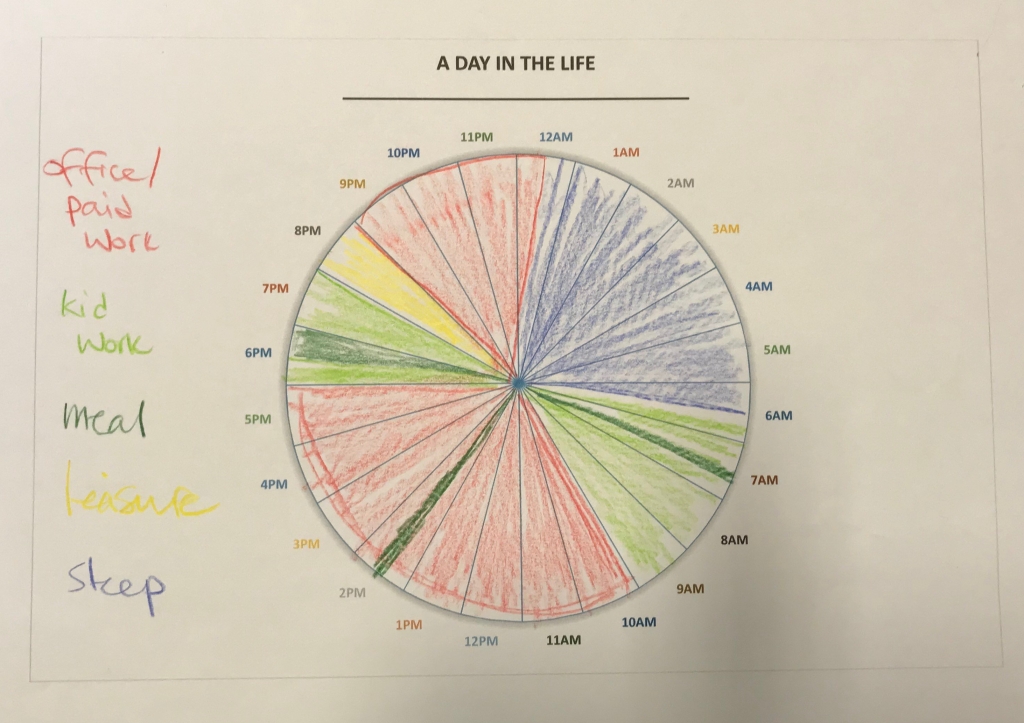

As part of the activity I invited participants to plot their own ‘average working day’. Adults, children and teenagers all got involved, colouring in blank templates of my 24-hour pie chart. They tracked how much time they spent travelling, at work/school, or enjoying leisure time. While some clocked up lengthy hours at work, many were surprised to see that they spent comparatively little time in the office, though some noted they continued to check emails once home. I enjoyed chatting to kids about how they divided their evenings between homework and ‘screen time’ and the role their parents played in regulating this. After completing their pie charts many participants reflected that they had a better time than the Victorians! Though they also spotted plenty of parallels – such as how the boundaries between work/leisure time might be blurred or how ‘free time’ might be circumscribed by the expectations and rules of others.

A parent tracks how much time they spend on 'paid work' and 'kid work', with a sliver left for 'leisure'.

Finally, my activity also invited any visitors with their own experiences of life on the shop floor to share their (modern-day) retail work horror stories. While some had fond memories of shoplife, I was surprised and shocked by some of the awful tales I heard. A major theme was rudeness and harassment from customers. One person said that a customer had hurled a chair at them because they didn’t like queuing, while another reported that, at Christmas, a stressed shopper had thrown brussel sprouts at them because the shop was out of brie. One person recalled being ‘spat on and violently prodded’, while several (men and women) spoke about being propositioned by customers. Victorian shop workers, who were expected to be deferential to their customers, no doubt suffered similar horrors. Many of my participants also shared stories of minimal or non-existent breaks, long working days, and the excruciating tedium of working in a shop – one person described feelings of ‘emptiness’, while another said it was like a ‘living death’. This reminded me of a passage in Wells’s semi-autobiographical novel Kipps (1905), where the narrator describes how the titular character (a young apprentice in the drapery business) ‘plumbed an abyss of boredom, or stood a mere carcass with his mind far away’.

Victorian Speed Event at Museum of the History of Science by Ian Wallman

'Death and Disease Behind the Counter' was a great activity to get people talking about the lives of shop workers then and now. Having visual materials and a hands-on activity enabled me to have more in-depth conversations with people, and I was fascinated to hear people’s responses to the activity and their own insights into the pressures of shop work. One of the main myths busted was the idea that long opening hours were a modern invention – these were very much a product of Victorian consumerism!