Last weekend the Drinking Studies Network held its second major conference, ‘New Directions in Drinking Studies’ at the University of Leicester. The Network brings together scholars from a range of fields to explore drink from perspectives ranging from the sociological to the literary. Far from being simply a euphemism for spending the weekend ‘studying’ in the pub, the weekend offered a full programme of papers that touched on everything from Welsh craft cider to champagne, middle-class domestic drinking to teen ‘pre-loading’, and Roman taverns to British village pubs.

A recurrent theme throughout the conference was how closely alcohol is tied to national identity and notions of ‘tradition’. The Welsh cider producers interviewed by Emma-Jayne Abbots all had specific ideas about what constituted an ‘authentic’ cider, and this often extended beyond simple ingredients to encompass broader working practices: the role of manual labour in the process, for example, might be looked upon very differently than the use of automated machinery. The role of technologies in drinking cultures was also evident in papers addressing earlier periods and other countries. The traditional Mexican drink of pulque (made from the agave plant), discussed by Deborah Toner, had a short shelf life so that it was easily usurped in the 20th century by tequila, replacing pulque as the ‘national drink’ of Mexico.

‘Tradition’ might be a badge of honour or distinction, then, but several papers demonstrated that some ‘traditional’ drinks have also been viewed in a more negative sense. Andrew Primmer and Daniel Plata presented a fascinating history of chicha, a Colombian drink derived from maize. In the early 20th century chicha struggled to hold its own as the German Bavaria Brewery muscled in on its territory. Newspapers and public information posters began to warn drinkers against chicha, aligning the drink with crime and ill health. One brand of beer was explicit in presenting itself to consumers as a better alternative, its name literally translating as ‘No More Chicha’.

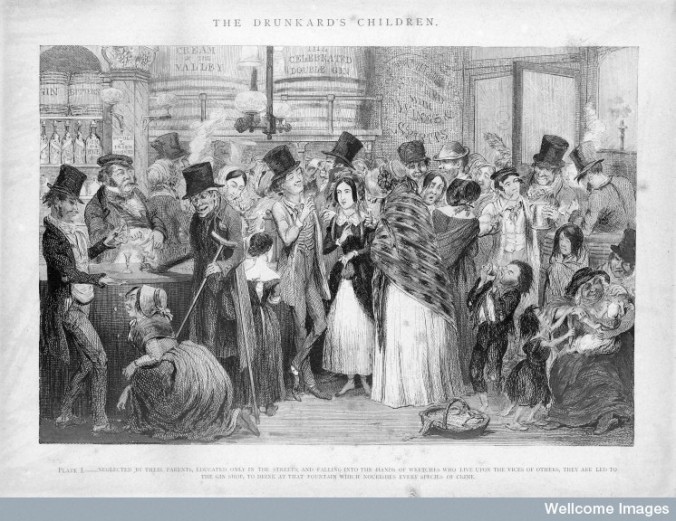

Consumers, of course, were at the centre of much of the weekend’s discussions, and alcohol’s potential for harm was examined across various periods and countries. There were obvious historical parallels between the middle-class drinking ‘subcultures’ of today, discussed by Lyn Brierly-Jones, and my own work investigating late 19th-century concerns for the lady ‘secret drinker’, with both figures provoking lively comment in the press. Perhaps what was most striking when looking at the conference papers as a whole was that, though ideas and perceptions of alcohol are very much shaped by the social and cultural context within which drinks are (or are not) consumed, the same concerns recur repeatedly: that alcohol might be consumed secretly, disrupt working practices, or harm the national health. Such concerns are often magnified in times of stress, as Stella Moss described in her paper on women workers during WWI. Moves to restrict women from entering pubs during certain hours reflected anxieties about wartime production, but also about the absence of husbands (away at the Front) as a ‘moralising influence’.

Alcohol, then, is very much bound up with our personal identity. This might be a simple matter of the drink one chooses (the more ‘ladylike’ glass of wine during a sophisticated night out, for example, as Carol Emslie et al touched upon), but can also be extended to encompass whole nations (the appeal to patriotism in the marketing of AB-InBev’s Siberian Crown lager, discussed by Graham Roberts). It is a means of exploring those identities, but also – in its ability to transform the consumer both mentally and physically – a means of cultivating multiple identities, or even, perhaps, of ‘recovering’ an authentic self. Perhaps it is this that makes alcohol so enduringly fascinating and worrying in equal measure.

You can follow the work of the Drinking Studies Network via their website and on Twitter.