Victims of Civilization: The Stammerer's Identity in Victorian Britain

This is a guest post by Dr Josephine Hoegaerts, a Research Fellow at the Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies and the author of Masculinity and Nationhood, 1830-1910. Constructions of Identity and Citizenship in Belgium. Josephine runs a blog a Singing in the Archives and is currently writing a monograph on the changing social ascriptions to the speaking and singing voice in Western Europe, tentatively entitled Speakers, Stammerers and Singers. A Social History of the Modern European Voice.

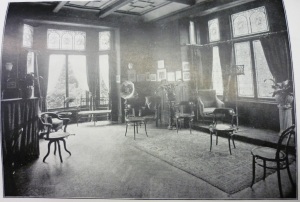

The ‘lecture room’ at Tarrangower. (W.J. Ketley, Stammering: The Beasley Treatment, Birmingham: Hudson and son, 1900.)

Around the turn of the 20th century, Tarrangower, an ‘Establishment for the cure of stammering and all defects of speech’ was founded on the outskirts of London. Its director, William Ketley, ran the establishment with his wife and daughters following the principles of a stammering treatment set out by his father in law, Benjamin Beasley. It was advertised as a wholesome family business, where ‘resident and non-resident pupils’ alike could expect to be cured of their embarrassing impediments. Tarrangower, as it was depicted in Ketley’s book-length account of ‘The Beasley Method’ was a picture of late-Victorian refinement and domesticity. Its airy lecture-room offered a view over the wide grounds and even boasted a gramophone, a sure sign of the establishment’s modern aspirations and innovative approach to pedagogy, therapy and entertainment. In fact, Tarrangower and the Ketley-Beasley family seemed to present themselves as the advocates of an explicitly modern and new understanding of stammering and the stammerer’s identity. In the introduction to Stammering: The Beasley Treatment (1900), Ketley characterized the stammerer – his potential client or pupil – as a strong master of his own fate.

"Among all men in the world there are none as a class who are better equipped in mental abilities, in versatility, in depth of penetration, in nervous force, than the stammerer."

The latter part of that sentence, especially, signaled a departure from earlier interpretations of stammering. Throughout most of the nineteenth century, the impediment had been understood as a nervous disease, comparable to other afflictions that entailed involuntary movement, like chorea or St Vitus's Dance. Stammering was thus essentially heard as speech interrupted by the twitches and contractions of an unruly tongue, caused by an inability to control one’s own body due to some weakness of the nerves (or indeed of character, as some authors seemed to suggest). The affinity between stammering and nervous disease was a puzzling one for nineteenth-century scientists and therapists. Nervous afflictions were generally understood to be a ‘feminine’ pathology, but the statistics that were compiled on stammering throughout the century showed that women were far less likely to stammer than men. Experts disagreed on the exact percentages (some claiming that women did not stammer at all, while others thought up to one third of stammerers were female), but they were unanimously stumped by this anomaly in nervous pathology. Explanations were sought, rather unsuccessfully, in women’s anatomy (their smaller larynxes would make speech easier), and in their loquaciousness (giving them more practice in developing fluent speech).

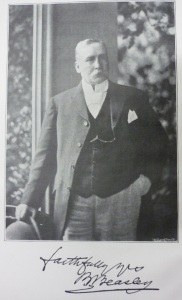

It was only toward the end of the century that the paradox of the male stammerer was resolved. In the 1870s, a new type of expert emerged in the field of speech pathology. After a long period of territorial conflicts between physicians (often depicted as heartless butchers, overly keen to cut into stammerers’ vocal organs) and therapists (often ridiculed for their lack of medical expertise and denounced as quacks), a happy medium was found between medical and educational approaches to speech impediments. Benjamin Beasly was one voice among a new generation of experts who explicitly combined the results of scientific medical research and educational practice in their work. Considering the stammerer neither as a patient to be observed and cured, nor as a nervous weakling unable to control his tongue, Beasley proposed a series of exercises that explicitly mobilized the self-discipline he expected his ‘pupils’ to have. His main claim to expertise on the subject was his own experience of stammering. According to his Reminiscences, Beasley had been an inveterate stammerer who had fruitlessly tried out all cures until he finally devised his own method to obtain fluent speech.

“My own personal experience unquestionably proves to me how fearfully one may be afflicted with the impediment without having reason to attribute it to nervousness. As a child I was very healthy and robust, and at the age of five or six years was remarkable for my fluency of speech and perfect articulation.” (Benjamin Beasley, Stammering: Its Treatment, London: Waterlow and Sons, 1888).

Proudly claiming an identity as a stammerer (albeit a ‘cured’ one), Beasley redefined the socio-cultural understanding of stammering, and solved the paradox of the stammerer’s gender. That especially white middle-class men were prone to stutter, he surmised, was not a result of their nervous weakness, but rather that of their great intelligence and of the demands modern life made of the strongest, most civilized members of society. Those free of responsibilities connected to business and politics (and the need for fluent speech these entailed) were less likely to stammer. And therefore children, women and ‘savages’ were generally blessed with uninterrupted speech patterns. His son-in-law reiterated the reasoning in his advertisement for the Beasley method, devoting a whole chapter to the observation that stammering was a ‘product of civilization.’

"The child of the savage is brought up like a healthy little animal, [… ] knowing nothing whatever of the repressions which count so much in the decencies and refinements of conduct among civilised peoples. […] How different, when compared with this, is the every-day training of the child brought up in a civilised environment. From the very first day on which he can by word of mouth make his wants known he is taught to whisper of the most intimate things, to disguise his real instincts[…]. And so his animal spirits and vitality being suppressed, kept in check, forced back upon him, neurotic conditions are engendered. He learns to be ashamed of his natural instincts; […], becomes neurotic and nervous; hesitates in making his wants known, blushes when asking favours, and finally, where the temperament is especially highly strung, and the predisposing causes exist, becomes a stammerer – a victim of civilisation."

Was the robust, self-made male stammerer, so eminently capable of overcoming his own impediments neurotic and nervous after all, then? Perhaps, but only – according to Beasley and Ketley, because his ‘nervous force’ was so great and his intellect so exceptional.

--Josephine Hoegaerts