There is a well-known anecdote about an appearance Peter Sellers made on Parkinson many years ago. Backstage before the interview, Sellers realised that the show’s format required him to appear in front of a live audience without the distance of a character between him and them. “I can’t do me!” he expostulated to his host. The eventual compromise involved Sellers goose-stepping onstage in a German greatcoat and army helmet, before performing a striptease to get out of the costume, whereat he assumed the character of an incompetent magician for a few moments, then finally settled down into apparently being Peter Sellers. To what extent that too was a mask is something only Sellers could have answered. If indeed he knew.

Our identities can be difficult to pin down at the best of times, but never more so than at those moments when we are acutely conscious that we are presenting a persona to the world. For performers, for whom this is a nightly occurrence, a tricky balance must be struck between how much of their inner selves and how much of their artifice is on display. It is the ambiguity as to which, or how much of each, we as the audience are privy to at any given moment that makes the great performers so compelling. At their most sublime, we witness the forging of a perfect alloy of expression and technique. To observe this process at work, however, we must look at instances of the extraordinary, where something has gone awry from the usual course, where, for instance, the self has become obliterated and the spotlight shines only upon an empty costume. This brings us to the curious case of the psychic pianist, Benjamin Henry Jesse Francis Shepard (1848 –1927).

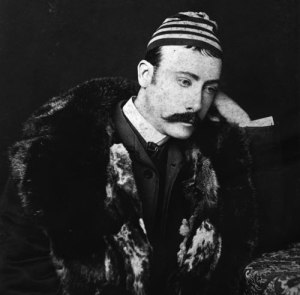

An English-born American, one might be tempted to blame the nominal proliferation for the uneasiness of his grip on his identity. He also wrote under the pen-name of Francis Grierson, and composed as well as performed music. His wholly spontaneous performances, on vocals and piano, were like no other, in that he did not claim to be the source of his own improvisations. Rather, he said, he was a mere channel for the spirits of dead composers. Through him, Chopin, Mozart, and Liszt, among many others, assumed control of the piano and took advantage of the rare opportunity to treat audiences to encore performances from beyond the grave.

Not surprisingly, Shepard was heavily involved in the occult. He was a friend of the Theosophical Society’s co-founder, the notorious Madame Blavatsky, and his performances were billed as part of the Spiritualist project. Like Blavatsky, he believed that an invisible spiritual realm co-existed and at times co-mingled with the material world, and that it could be partly accessed by those able to occupy the borders between them. To him, music was not a medium for self-expression, but a medium for accessing the transcendent. ‘Music’, he wrote in his study of the Celtic Temperament, ‘is a metaphysical illusion, whose secrets are often felt but never uttered’.

By all accounts, Shepard’s performances were utterly compelling and even mesmerising. By his mid-twenties, he had travelled extensively, giving performances across America and Europe. His unusual approach to his art, if one discounts the likelihood of his actually channelling dead composers, might be seen as an extreme embodiment of the kind of relations between living artists with the great monuments of the past that Eliot postulates in ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’: “What happens is a continual surrender of himself as he is at the moment to something which is more valuable. The progress of an artist is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality.”