A man lies dead or unconscious in his chair, his last glass of drink fallen from his hand. Lithograph by Lamy, c. 1860, after Villain. Wellcome Library, London.

I’ve been doing a lot of work on lady secret drinkers recently (such as the eau de cologne tipplers I devoted a previous post to), but a question from the audience at a talk I gave a few weeks ago reminded me that, somewhere in my office, was a file of other 19th-century problem drinkers – namely, male professionals.

Digging around in a filing cabinet, I found the surreptitious tipplers I was looking for. These were ‘respectable’ problem drinkers who occupied responsible positions – men who incorporated alcohol into their lives without their habit being obvious to the casual observer. Lawyers and their clerks were common points of concern. In 1871, the Saturday Review railed against what it termed ‘counting-house alcoholism’, declaring that ‘men who shr[a]nk from going to one of the public bars ha[d] no scruple about fitting up a neat mahogany cellar in their own office’ and all too often resorted to the ‘forenoon specific’ of a biscuit and a glass of sherry.

‘Soakers in the City’, as The Lancet called them, were said to be all too common, but there were also worries about those professional men whose habits were less easily detectable. Literary men, doctors, and the clergy were particularly at risk, as their intellectual labours overtaxed their brains, ruined their appetites, and disturbed their sleep, leading to the use of stimulants:

‘The clergyman, the Christian worker, or the physician, after an exhausting day spent, O, how wearily! in listening to long dreary accounts of interminable wrongs and ailments … is so prostrate that he cannot even look at the food which his badly used stomach so sorely needs… An intoxicating stimulant in a few seconds dissipates every sense of fatigue, seems to infuse new vigour into his veins, new life into his fainting spirit, so that he can sit down comfortably [and] heartily enjoy a good dinner.’

The above quote from an 1884 speech by Norman Kerr, President of the Society for the Study and Cure of Inebriety, highlights how alcohol was often used to revive a flagging body and tired mind. It was the frequent use of alcohol in this way, though, that led the scholar or doctor to become reliant upon his favourite tipple. Within discussions of the ‘solitary midnight inebriate’, clergymen were prominent figures, and their drinking habits special sources of shame considering their calling:

‘I can scarcely conceive of a state more miserable [wrote the doctor]. Secret intoxication lasting only for a night, to be followed in the morning by the semblance of normal life … Carrying with him the image of the scene he cannot forget, and yet wishing the hours to hasten on, that he may cast aside the mask, and, behind the locked door, the bottle, the drink, and the narcotism, may rest him again for another day.’

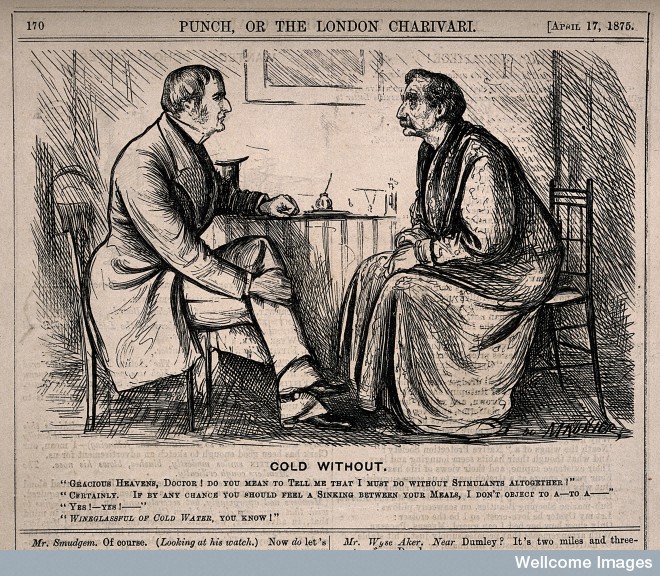

Drink had enveloped the clergyman in this case in a ‘moral mirage’, as the doctor put it. As people entrusted with the innermost secrets of their parishioners, the possibility that a member of the clergy might have a secret drinking habit was deeply concerning. One doctor related that he had treated several clergymen for alcoholism and that 90% of them had been led into the habit due to working too hard. Overwork was thought to affect many men involved in ‘brain work’ in the 19th century, and is a theme that frequently recurs throughout the Diseases of Modern Life project. In self-medicating with alcohol to meet the pressures of modern life, even the most well-intentioned individual could find themselves caught in a vicious cycle – much better, advised doctors, to reach for a handful of raisins or a glass of water than the brandy bottle when fatigue set in, as unenticing as those replacements may have been…

A patient dismayed at his doctor’s advice not to drink any alcohol. Wood engraving by G. Du Maurier, 1875. Wellcome Library, London.