Nerve-Exhausted but not Insane: Therapeutic Travel for the Over-Taxed Brain Worker

This is a guest post by Dr. Jennifer S. Kain, a Junior Research Fellow at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London, and author of ‘The Ne-er-do-well: Representing the Dysfunctional Migrant Mind, New Zealand 1850-1920’ (Studies in the Literary Imagination, 48:1, 2016). Jen completed her PhD entitled ‘Preventing Unsound Minds from Populating the British World: Australasian Immigration Control and Mental Illness, 1830s-1920s’ at Northumbria University in 2015.

In the nineteenth century the temperate parts of Australasia were imagined as therapeutic destinations for wealthy invalids. ‘Ordinary’ migrants seeking assisted passages, on the other hand, were expected to be sound of body and mind, sober and industrious. Likewise, self-paying passengers were subject to immigration controls which, in theory, identified those likely to become public charges. These bureaucratic regulations existed alongside commercial attempts to attract moneyed health-seekers to these regions. Shipping companies promoted their destinations, and the voyage itself, as restorative for those suffering from what we might call today anxiety disorders. Antipodean voyages on modern steam-liners were marketed as the ideal way of escaping from the stresses of professional lives in polluted British cities.

This promotional trope emerged in the latter two decades of the nineteenth century. In 1890 Dr. John Murray Moore recognised how, in this ‘new travelling age’, it was fashionable for doctors to send ‘nerve-exhausted’ patients to New Zealand or Australia, chiefly for the sake of the voyage. ‘Globe-trotters’, he enthused, were benefitting from conditions on the modern steam-liners and from the reduction in fares due to the commercial competition between shipping operators.

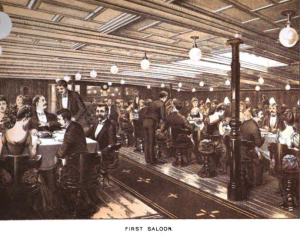

The Orient Line and the Peninsular and Oriental (P & O) Steam Navigation Company sought to capitalise on this ‘new age’. They created plush illustrated guides to promote their voyages as therapeutic, in particular for ‘brain workers of our large cities’. The P & O’s 1888 guide included a chapter entitled ‘The Ocean Cure’ which attributed this phrase to a recent article in the British Medical Journal. The author applied the descriptor ‘brain-worker’ to middle-aged men who spent long sedentary periods in a study or office. Clearly promotional in nature, the BMJ piece warned against the prevailing advice given to those with ‘exhausted nervous systems’ to go hunting or fishing. This type of violent muscular exercise, the writer warned, was likely to trigger an attack of acute disease. Instead, the professional man was far better taking a sea voyage through which to escape the post-office and the telegraph wire, thus restoring his exhausted energies.

Orient Line Guide: 1890 © National Maritime Museum

The Orient Line likewise promoted their voyages as especially beneficial to the ‘over-taxed or professional business man’ who, apart from dressing and eating, would ‘need undergo no mental or bodily exertion whatever’ on-board. The Orient Line’s own medical officer, James Struthers, equated the modern conditions on-board with technological and scientific theories. He enthused that, while the abundance of internal electric lights neither used up oxygen nor emitted fumes, the main benefit of the voyage was the time spent on deck. The atmospheric conditions - a combination of sunshine, ozone, sodium chloride, bromine and iodine - served to improve sleep and appetite. Such an environment was ideal for those medically advised to ‘rest their minds’. These types would find their capacity for labour improved accordingly.

Orient Line Guide: 1890 © National Maritime Museum

Struthers countered this positive spin with the warning that those whose mental disorder was ‘likely to cross the borderland between sanity and insanity’ should never be sent to sea. The same restful conditions for the ‘insane’ could prove fatal. While the melancholic, if not kept busy would ‘brood on his grief’, those contemplating suicide were constantly reminded of how easy it would be to throw themselves overboard.

This caution reflects an interesting parallel with the concern expressed by colonial administrators that the voyage itself triggered ‘latent insanity’ in migrants. This idea, which emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, was associated with the fear that certain migrants carried ‘transmissible defects’. And yet, while early twentieth-century Australasian immigration restrictions sought to keep out the ‘defective’, wealthy professional men were not considered in such terms. Those ‘fleeing from worry and strain’ remained feted as the ideal passenger.

The increasing medical attempts to codify levels of mental and moral disorder were reflected in Dr Elder’s The Ship-Surgeon’s Handbook (1911). Elder acknowledged that most patients, including the ‘business man’, were sent to sea due to neurasthenia. The therapeutic success of the voyage was determined by the choice of ship, season and route. The ‘overtired and overworked’ man, Elder advised, should travel on a full ship. This gave him the opportunity to take part in social activities to distract him from his worries, or, if more preferable, seek out similar types with whom to ‘foregather quietly’. Additionally the time and medical facilities on-board allowed him to undergo minor surgical operations, such as the removal of varicose veins.

It is interesting that the so-called ‘nerve-exhausted’ men were credited with the mental capacity to make such decisions as how to best spend time on board. These types were deemed the most likely to convalesce from the stresses caused by the overload of modern life. Those of a different class, vocation, and gender were not seemingly classed as a significant marketing demographic, nor were the ‘properly insane’.

--Jennifer Kain

Sources

Vavasour Elder, The Ship-Surgeon’s Handbook (London: Bailliere, Tindall & Cox, 1911)

Miles Fairburn , The Ideal Society and Its Enemies: The Foundations of Modern New Zealand Society, 1850-1900 (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 1989)

John Murray Moore, New Zealand for the Emigrant, Invalid and Tourist (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1890)

Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company’s Pocket Guide (London: Nissen & Arnold 1890)

Orient Line Guide: Chapters for Travellers by Land and Sea (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1890)