‘Inside Passengers; or, the Wonderful Adventures of Luke and Belinda’ was a 15-part series published in The Girls’ Own Paper in 1885-86, penned by ‘A London Physician’. Anticipating the plot of films such as Fantastic Voyage (1966) and its later comedy spin-off Innerspace (1987), the series follows brother and sister Luke and Belinda on a journey through their uncle’s body after they are shrunk by some gateaux evanouissants (vanishing cakes) bought from a seller of Eastern curiosities. Seeking out their uncle after this catastrophe, they manage to clamber onto the arm of his glasses but are accidentally swept into his mouth after falling into his moustache.

The shrinking motif immediately calls to mind Alice in Wonderland, published 20 years earlier, and no doubt the author had the book in mind as he plunged his characters not down a rabbit hole, but down the oesophagus. The series had a serious aim, however. Published in a periodical aimed at young female readers, it repeatedly emphasises that scientific knowledge is something of use to everyone. Belinda laments that ‘it is shameful that we girls are taught nothing about our ‘insides’’, and her brother Luke – who has just passed his final exam at the College of Surgeons – proves a perfect guide to the subject. Getting over their initial horror at their predicament surprisingly quickly, the two relish the opportunity to explore their uncle’s internal landscape. Beginning in the mouth, they progress to the ear, throat, and stomach, though no doubt for reasons of propriety they go only as far as the duodenum before turning back and making their exit through the pores of the skin.

The story is part adventure story, part biology lesson, with a bit of moralising thrown in. Luke – equipped with binoculars, electric lamp and a pick – leads them in their exploration of the body’s terrain and ‘like Robinson Crusoe … [begins] to regard his uncle as his own private property’. One of his first activities inside his uncle’s mouth is to chisel out some nuggets of a gold filling, reasoning that if they are restored to their normal size then a few millimetres of gold will increase in size to make them millionaires. Interspersed with this adventure narrative are short lessons on the body, delivered by Luke in a rather self-congratulatory fashion to his eager listener, Belinda. Both she and the reader learn about the Stenson’s duct delivering saliva to the mouth (a lesson interrupted by their uncle partaking of a cigar and transforming the mouth into a ‘smoking-carriage’); the taste buds; the larynx and vocal cords; the cochlea; and the villi of the intestinal lining. Some of these lessons include general health advice to the reader: on the importance of brushing teeth at night rather than in the morning, and chewing food thoroughly to aid digestion.

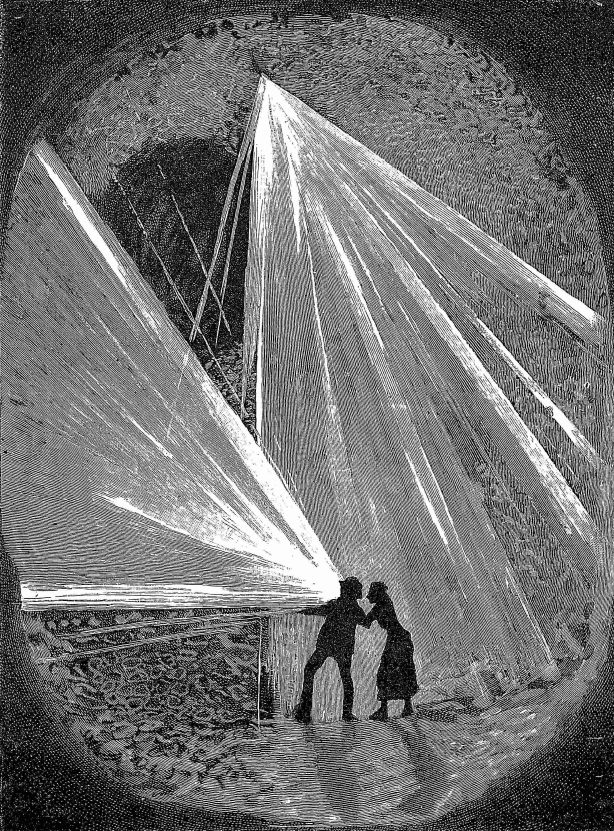

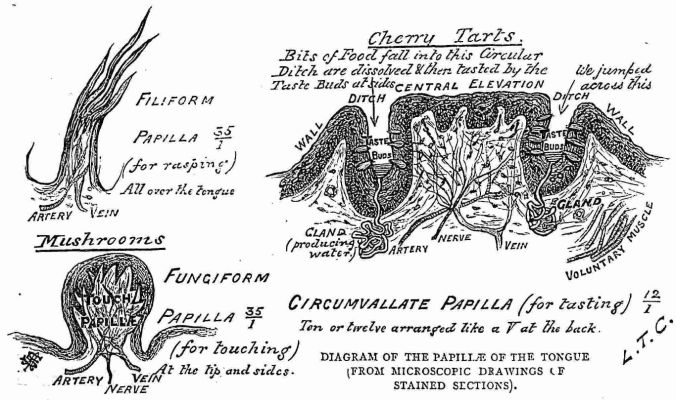

The text is accompanied throughout by some striking illustrations, several of them by Harry Furniss, who worked for Punch and would go on to illustrate Lewis Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno. Many of these pictures present the body as a cavernous landscape with Luke, Belinda, and their friend Sutton (who has also eaten some of the vanishing cakes and is conveyed into the mouth on their uncle’s handkerchief) scaling walls or peering into yawning abysses. These are complemented by scientific illustrations, including a cross-section of the mouth and throat, and magnified villi. As Belinda and Luke examine the tongue, the description of its features again echoes the fantasy world of Alice: ‘mushrooms’ are the fungiform papillae (to ‘tell you at once’, explains Luke, ‘if your cup of tea is too hot’) and ‘cherry tarts’ the circumvallate papillae for tasting. The accompanying illustration helpfully melds this literary description with more scientific language, allowing the reader to visualise the features clearly.

The trio’s investigation of the interior body lasts for a full week, and getting around the issue of quite how the three survive in this environment are some novel technologies that Luke has handily purchased from a ‘scientific novelty shop’ shortly before their shrinking. They survive on ‘H.F.D. (hospital full diet) pills’, each containing ‘as much nourishment as there is in twelve ounces of bread, eight ounces of potatoes, six ounces of roast beef, and one pint of porter’, and a ‘C.C.W. (chemically combined water) flask’, which forms water from a combination of gases and holds the equivalent of 1,000 gallons. (I’m particularly taken with the ‘coffee tablet, containing the amount of coffee, sugar, and milk to make one cup’.) Keeping them dry amidst their uncle’s saliva and stomach juices is a ‘waterproof powder’, forming a film of gutta-percha over their clothes, and a ‘degravitator’ alters the weight of the gold Luke has mined from uncle’s tooth, allowing them to carry it with ease.

The technical elements of the story are nicely balanced out by Belinda’s romantic observations of the interior of the body. She describes the cilia – like ‘ripe corn waving backwards and forwards in the breeze’ – as ‘live velvet’ and christens the inside of the ear ‘the organ loft’. Though she welcomes her brother’s medical teaching, she finds his ‘rubbishing affectation’ a nuisance, substituting his medical terminology for her own down-to-earth descriptions that are more memorable for the reader. The story has a distinctly unsettling quality too, though, as the characters find themselves at the mercy of their uncle’s eating, drinking, and smoking habits (‘I’ve no fancy for being digested’, exclaims Belinda as they traverse the stomach). As tiny elements within the body, then, the characters highlight to the reader the importance of considering what they put into their bodies – not least when Belinda is nearly drowned in a ‘dreadful whirlpool’ of beer or choked by her uncle’s cigar smoke. It’s a wonderfully creative play upon the advancing sciences of microscopy and bacteriology, and a lovely example of how scientific teaching could be incorporated into fictional narrative for a young audience. I only wish I knew who’d written it; I’ve no idea who ‘A London Physician’ was, so if any readers have then please do let me know in the comments section!